I have a habit of transcribing recorded conversations and passages from books as a way of gleaning a more in-depth understanding of a subject. There’s something about transcribing for me that aids in the digestion of certain concepts that enter my brain in that specific manner.

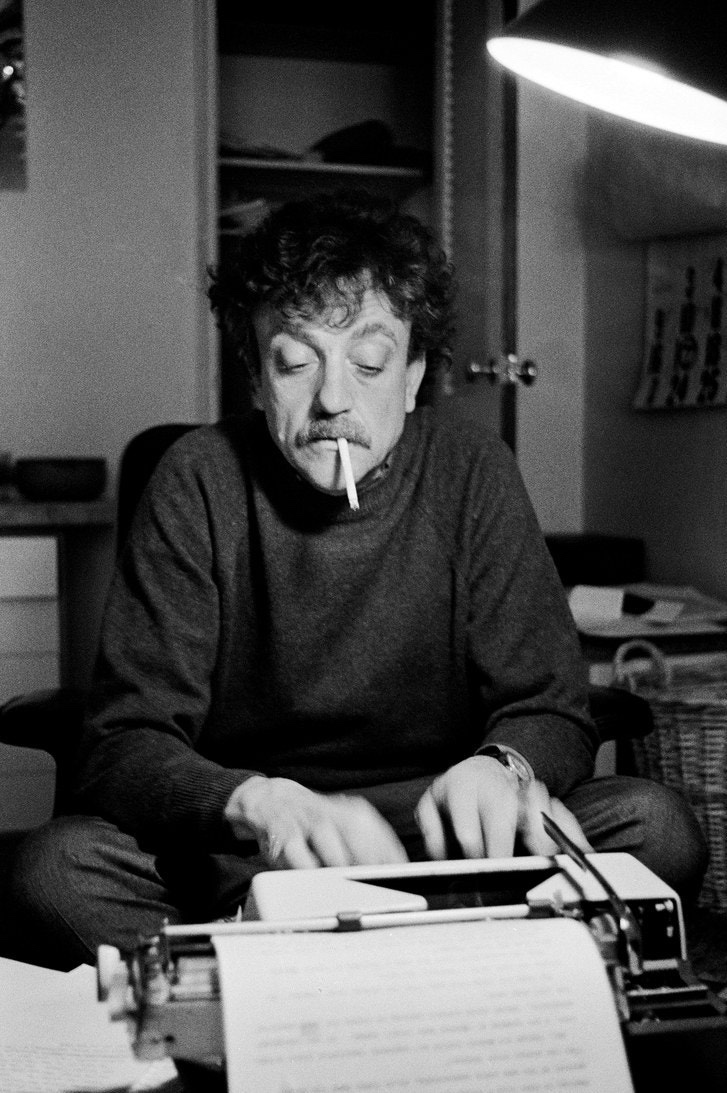

There’s a chapter in Kurt Vonnegut’s book, Cat’s Cradle, wherein the narrator asks a “vacantly pretty” woman of twenty named Francine Pesko—who is introduced to him by a Dr. Breed as the secretary for a Dr. Nilsak Horvath, a famous surface chemist “who’s doing such wonderful things” with films—the question: “What’s new in surface chemistry?”

“God,” she said. “don’t ask me. I just type what he tells me to type.” And then she apologized for having said, “God.”

“Oh, I think you know more than you let on,” said Dr. Breed.

“Not me.” Miss Pesko wasn’t used to chatting with someone as Dr. Breed and she was embarrassed. Her gait was affected, becoming chickenlike. Her smile was glassy, and she was ransacking her mind for something to say, finding nothing in it but used Kleenex and costume jewelry.

Since Cat’s Cradle was published in 1963, we can say that Miss Pesko’s attitude was not unusual for the era, but the excuse just doesn’t hold up for me when I think of my grandmother, who was a medical transcriptionist in 1963 and forty-one years old at the time.

My grandmother soaked in the knowledge she gained from transcribing and decades later, when I was an adult, she would rattle off medical facts in conversations that made her sound like she, herself, was a seasoned medical professional.

I’m very much like my grandmother in that way. In fact, I consider myself a knowledge junkie. And, I don’t understand how people can affect an attitude of willful ignorance about things with which they are in daily contact.

There’s no excuse to remain ignorant when most of us have access to a tremendous body of knowledge at our finger tips.