When American President Donald Trump announced his ambitious plans for a Mars mission during his first term, my instincts as a journalist led me straight to the source—though this source was orbiting Earth in a spaceship. The Martian ambassador, a wiry figure with an otherworldly aura, answered my Skype call, looking both annoyed and flustered.

“We weren’t expecting you people to visit Mars for at least fifteen years,” they snapped, annoyance crackling through the connection like static. “We’re not ready.”

Beside the ambassador, stood a pilot and an anthropologist, both with expressions that could only be described as galactic exasperation.

“We can’t yet protect ourselves from your viruses,” the anthropologist chimed in, her voice carrying the weight of countless microbial concerns. “And we’re just learning about the effects of Martian viruses and microorganisms on human physiology.”

The pilot, apparently not one to miss a chance for a sarcastic jab, leaned forward. “We also haven’t received the funding your leader promised for the construction of his 200-storey luxury hotel in our capital city,” he said with a smirk.

“He’s joking,” the anthropologist cut in, rolling their eyes. “Earth people are presently much too xenophobic for a successful first contact. Also, we build our cities underground.”

The word “xenophobia” hung in the air and I couldn’t help but recall the many films that have showcased humanity’s fear of aliens and the unknown. In District 9, for instance, aliens are segregated and mistreated, a grim reflection of human prejudices. And then there is Arrival, a recent movie that shows the paranoia and mistrust that greet visitors from another world, echoing real-world anxieties. Even the classic E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial underscores how quickly fear can turn to hostility.

Curious about their intel, I ask the Martians if they had monitored the conversation Trump had with astronaut Peggy Whitson earlier this year while she was aboard the International Space Station.

“Actually, we heard about Trump’s plan while listening to NPR over the radio,” the ambassador replied. “My crew prepared a skit for the folks back home. Do you want to see it?”

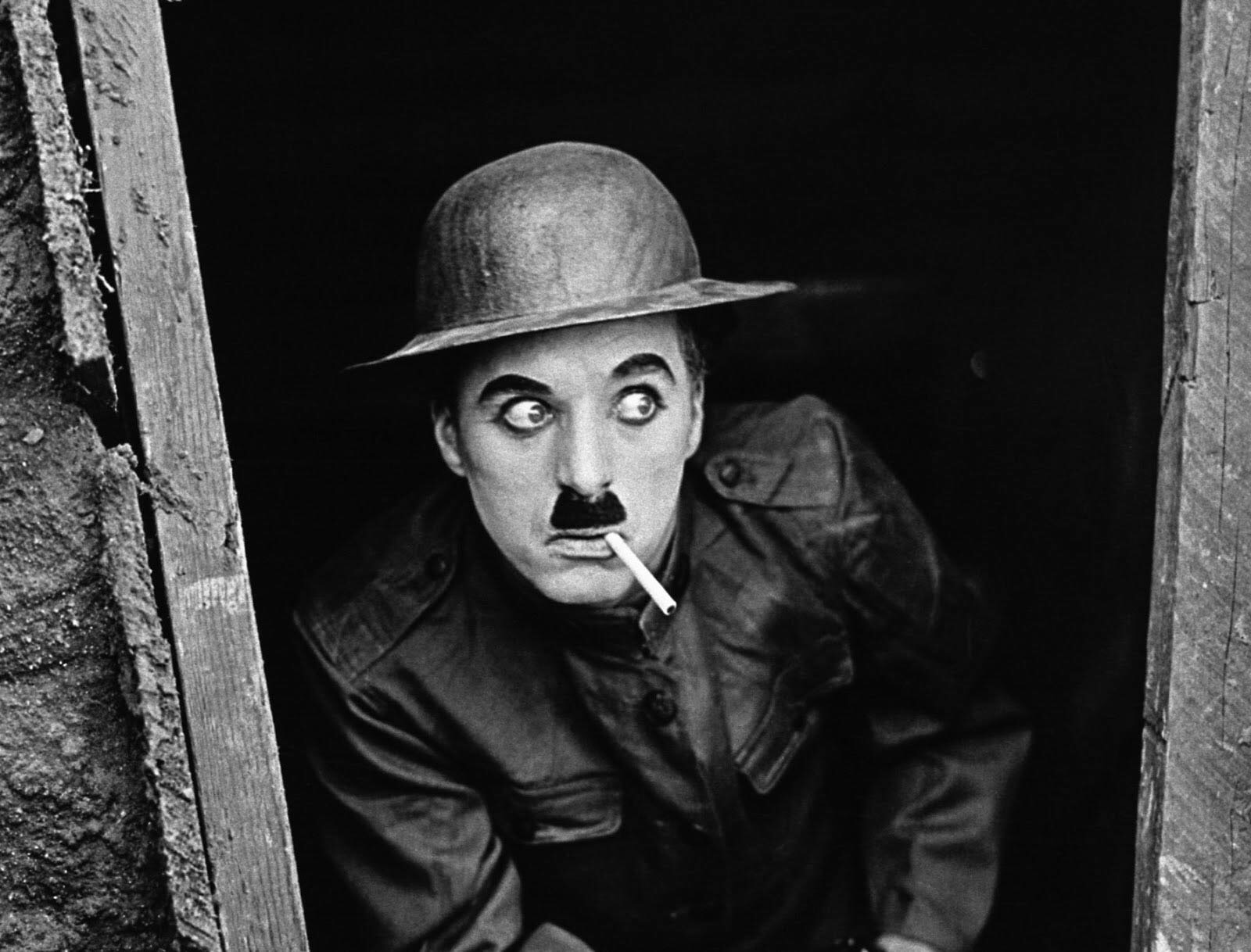

I nodded, unable to resist the promise of extraterrestrial satire. The pilot’s skin began to ripple and shift, turning a familiar shade of orange as he morphed into a perfect doppelgänger of the current American president.

“Tell me, when are we gonna go to Mars?” he demanded, his parody an uncanny mix of Alec Baldwin’s Saturday Night Live impression and the real deal.

The anthropologist, now resembling Dr. Whitson, sighed dramatically. “You already approved a timeline for the mission to safely launch in 2033.”

“Well, we want to try and do it during my first term, so we’ll have to speed that up a little bit, okay?”

“But, what about the construction of your golf course on the sun?” she retorted.

“We’ll be doing that at night so nobody gets burned,” the pilot shot back, his face a study in deadpan seriousness.

As the two Martians shifted back to their natural forms, they high-sixed each other, laughter echoing through the ship. Their comedic timing was impeccable, in contrast to the absurd reality unfolding back on Earth.

Yet, beneath the humor, the real challenges and expenses of mounting a mission to Mars loomed large. NASA estimates that a manned mission to Mars would cost upwards of $100 billion. The technical hurdles are equally daunting: ensuring safe passage through deep space, developing habitats that can protect astronauts from cosmic radiation, and finding ways to produce food, water, and oxygen on the barren Martian landscape. Not to mention the psychological toll of a years-long mission in the claustrophobic confines of a spaceship.

The ambassador’s concerns weren’t just bureaucratic griping; they were grounded in the harsh realities of interplanetary exploration. Every step forward requires meticulous planning, technological innovation, and international cooperation—a far cry from the slapdash, spur-of-the-moment decisions that seem to characterize much of modern politics.

As our call ended, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this Martian skit, as humorous as it was, captured a deeper truth about humanity’s place in the cosmos.

We may dream of the stars, but we still have a lot of growing up to do before we’re ready to reach them.

Like this:

Like Loading...