I’m in Eugene for a week after leaving my job at a Telegraph Avenue shop called the Yarmo Zone, wedged between Blondie’s Pizza and Sather Gate World Travel.

The Zone is a quirky Berkeley shop facing Caffé Mediterraneum that sells Betty Boop paraphernalia, pin-back buttons, silk skinny ties, and a medley of mod-to-punk ephemera.

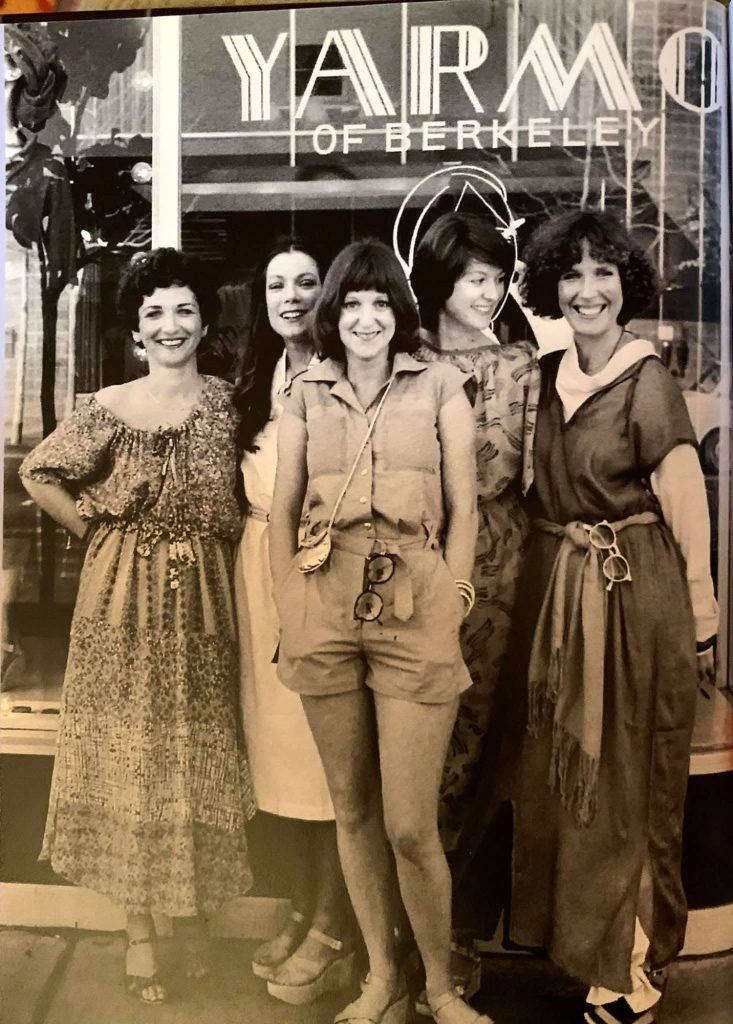

It’s an offshoot of Eva Yarmo’s boho clothing boutique across the Avenue, the one she opened in the mid-sixties when Telegraph was still a runway for miniskirts and the first wave of countercultural fashion.

Everyone has an opinion about my plan to join the Air Force. My friends and family are shocked and appalled that I would enlist, but the logic of my decision makes sense to me. Lenny bluntly tells me I’m “just not the type for wearing the uniform,” and I get the heart-to-heart from Joyce’s husband, Lee, a Vietnam vet. We meet at the nosh bar and he’s painfully earnest as he tries to convince me that the military isn’t the place for an idealistic kid raised in the counterculture.

I lay it all out for Lee and tell him I want to learn the Russian language. I’ve been following the cultural shift in the Soviet Union, and I believe that with the rise of computers and the impossibility of controlling the flow of information, Russia can’t stay sealed off forever.

I insist that attending the Defense Language Institute is my ticket to becoming a diplomat someday. I’m sure the United Nations would more readily accept someone with military experience over a college drop-out, so enlisting seems the most direct path.

It’s chapter two of the Reagan-Bush era, and Ronnie Raygun is still calling Russia the evil empire. This sort of bullshit propaganda has got to change. And I want to be an integral part of that shift—to be on the front lines of making things better between our countries.

What I’m not telling everyone is that I’ve already enlisted, and I’ll be at boot camp next week.