This is a story about a place that no longer exists.

Not a business, or a single building, but an entire block—houses, shops, restaurants, bookstores, paths people took without thinking, rooms where conversations happened because there was nowhere better to be. The 600 block of East 13th Avenue is gone. In its place is a parking structure: concrete, efficient, anonymous.

The reason given was necessity. The justification was growth. The beneficiary was a hospital that no longer sits in the neighborhood it helped erase.

What disappeared wasn’t just square footage. It was a way of living lightly inside a city—former houses adapted rather than replaced, small businesses that grew out of need rather than capital, places where you could linger without being expected to buy much, or anything at all. It was a block that worked at human scale.

This isn’t an argument against hospitals, or even against parking. It’s an accounting. A record of what was here before it wasn’t. Before the language of inevitability took over. Before a street with a life of its own was treated as blank space.

I walked these blocks when they were still intact. I ate in those rooms, browsed those shelves, learned which doors mattered and which ones were just scenery. I didn’t know at the time that the whole thing would vanish. Almost no one does while they’re standing inside a place that still works.

What follows is not nostalgia. It’s documentation. A way of saying: this existed, this mattered, and this is how it felt before it was paved over and politely forgotten.

Sacred Heart Hospital, a prominent institution in Eugene’s University District, had been a constant presence for decades before the small businesses and informal community that later defined the 600 block of East 13th Avenue emerged.

By the 1930s, Sacred Heart had firmly established itself near East 12th Avenue and Hilyard Street. As it expanded, it became one of the city’s largest employers and most influential institutions. Its proximity to the University of Oregon shaped the surrounding neighborhood, creating a diverse mix of students, renters, working families, and long-standing homeowners, all residing within the campus and hospital area.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the streets surrounding the hospital—Hilyard, Alder, and East 13th—remained predominantly residential. Craftsman-style houses built in the early twentieth century lined these blocks. As university enrollment increased, many of these houses were converted into rentals, leading to a gradual shift from owner-occupied to increasingly transient housing.

By the 1960s, Sacred Heart’s physical footprint had expanded significantly, and its influence on nearby land use became more evident. Growth brought traffic congestion, parking pressure, and periodic construction projects. Streets were adjusted, and blocks closest to the hospital began to feel institutional. Despite these changes, the 600 block of East 13th—affectionately known as “the campus village” by locals—remained largely intact, separated from the hospital by a few blocks and marked by a noticeable shift in atmosphere. All the neighborhood needed now was a cool coffeehouse. Enter Vic Sabin.

Vic’s idea for the New World Coffeehouse did not emerge in a vacuum. Before coming to Eugene, he had been stationed in San Francisco while serving in the Navy, where he became immersed in the Italian-American coffeehouse culture of North Beach—the same cafés that had once served as informal headquarters for Beat writers, poets, musicians, and political talkers. Those spaces left a lasting impression on him.

When Vic later arrived in Eugene to attend the University of Oregon, he quickly became involved in the campaign to save the old College Side Inn, a beloved student gathering place slated for demolition to make way for the U of O Bookstore. The effort failed, and the loss was keenly felt. Rather than letting that disappearance stand as the final word, Vic channeled it into action. The New World Coffeehouse was founded, in part, as a response—a deliberate attempt to recreate a space for conversation, culture, and community that Eugene had just lost.

In 1964, the New World Coffee House opened on Alder Street between 12th and 13th as something entirely new for Eugene—a bohemian café in the spirit of Berkeley and San Francisco, a gathering place where music, art, poetry, politics, and everyday talk circulated freely around coffee cups and communal tables.

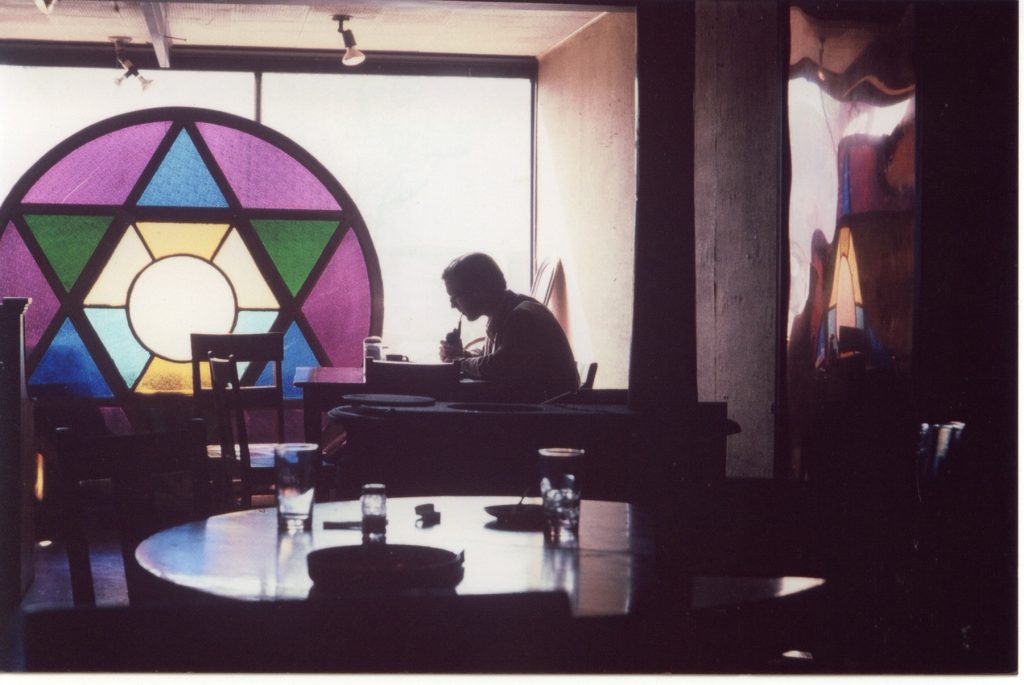

Inside, salvaged doors, stained glass windows, and wooden spools repurposed as round tables gave it a distinctive, lived-in feel, like someone had dropped a piece of the Fillmore District into Eugene. A funky old piano sat in one corner, and a large wood stove kept the place warm on chilly days, with customers often rising to throw another log into the fire themselves.

Most significantly, New World was the first café in Eugene to serve espresso, at a time when most coffee in town came in the drip or percolated diner style. It introduced freshly pulled espresso shots, handblown Chemex carafes, Torani syrups for specialty drinks, and its own signature creation, the Cappuccino Borgia—espresso with chocolate powder and orange peel, topped with whipped cream—that lived on in a few local coffeehouse menus long after the café folded.

Over the years, the menu expanded to include Hilda’s soups and sandwiches, omelets, bagels, quiche, pastries, and a legendary San Marino Chocolate Cake baked by Stephanie Pearl, who would later open her own café. New World was not just about drinks; it was about food as part of conversation, culture, and community.

In 1968, New World’s owner Vic Sabin sold the café to a group of University of Oregon professors who attempted to run it as an employee cooperative. Idealistic as that was, financial struggles soon followed.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, East 13th had developed a distinct identity. While still residential in nature, it increasingly supported small, informal businesses that emerged from former houses. These low-overhead ventures—ranging from food stalls and bookstores to craft shops and service providers—catered to both students and locals. The transformation was gradual and organic, occurring without a preconceived plan. Houses remained standing, and people adapted their interiors to suit new uses.

In 1971, Koobdooga Bookstore, owned by David Gwyther, was praised by the Oregon Daily Emerald as one of the best bookstores in town, not so much for its extensive stock, but for its meticulous selection. Located in a house at 651 East 13th Avenue, Koobdooga—a good book backwards—had an inventory that followed the interests of its patrons rather than sales trends. It featured philosophy, radical politics, Native American history, women’s studies, underground comics, and periodicals such as Zap, Bijou, Up From the Deep, Village Voice, Free Press, and Mother Earth News. Alongside these materials, it also carried items related to the Whole Earth Catalogue and works like Bob Dylan’s Tarantula.

The store’s narrow, vertical interior encouraged lingering. A magazine rack near the entrance led to shelves and, toward the back, crates of used records. The store bought, sold, and traded records, but books were its primary reason for existence.

By 1971, New World Coffee House placed a “Closed Forever” sign in the window, only to reopen months later under a leaner staff of friends led by manager Peter Winograd.

In the summer of ‘72, when I was a new kid in Eugene, I was exploring the streets, trying to figure out which doors mattered to an eight-year-old boy from Berkeley, California. The 600 block caught my eye, and Koobdooga pulled me in because a guy named Greg Weed was dealing comic books out of the back of the store. I was also drawn to New World because it reminded me of Caffe Mediterraneam on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, where I used to get Italian sodas when my mom was selling tie-dyed clothing on the sidewalk nearby. My dad and his girlfriend had recently decided to become vegetarians, and fortuitously that same year, Lee Boutell, a University of Oregon student from Kansas, turned the Craftsman house at 675 East 13th Avenue into a vegetarian restaurant called Eggsnatchur Natural Foods, usually shortened to Eggsnatchur or just the Snatch.

Eggsnatchur operated as a co-op, prioritizing affordable vegetarian food and long hours. Open seven days a week, it attracted students, locals, and people passing through town who quickly discovered its value for cheap, unpretentious meals. Its politics were subtly conveyed rather than explicitly stated. The food choices, pricing, and company of the patrons said enough.

By 1973, David Gwyther decided to step away from bookselling and sold the shop to Max Baker and Vic Sabin’s brother-in-law, Fred Austin, and they renamed it Son of Koobdooga.

By 1974, Greg Weed was burned out on selling comic books and sold his stock to Darrell Grimes, who added his own formidable collection and continued to operate out of the bookstore.

That second life of the New World Coffee House lasted a few more years, but by August of 1974 it finally closed its doors, marking the end of a chapter in Eugene’s coffee and conversation culture that had begun a decade earlier.

For a generation of students and locals, New World wasn’t just a place to get coffee. It was where you heard the latest political rumble, met someone who could sell you a zine or invite you to a reading, heard live music before a show, played chess on the courtyard tables, or simply found a quiet corner to think. It set a standard for what a coffeehouse could be in Eugene—more than a place for a cup, but a place for conversation.

When it closed, the vacuum it left helped create the conditions for what came next: smaller, more intimate spaces and the thriving, if improvised, café culture emerging off East 13th. New World’s legacy echoed in the espresso shots pulled elsewhere, in the handblown carafes and flavored syrups, and in the idea that coffeehouses could be forums for culture rather than just caffeine.

In 1976, Eggsnatchur transitioned out of the co-op model into single ownership under Lee and a partner, and was renamed Honey’s Café. The name changed, but the place remained essentially the same. It continued to operate as a house on 13th Avenue doing the work it had learned to do. That same year, in August, I moved permanently to Eugene, and Darrell moved his comic book collection into one of the small cottages behind Koobdooga at 667 East 13th Avenue and rebranded his business as The Fantasy Shop, a place I frequented after school for many years.

All these places formed a loose ecosystem along East 13th—businesses operating out of former houses, sharing the street with copy shops, cafés, and service-oriented storefronts that quietly supported a broader community. None of it felt provisional at the time, even though much of it was.

By 1978, Honey’s Café had closed, ending its six-year run as a vegetarian restaurant, and Poppi’s Greek Taverna opened in the same Craftsman house at 675 East 13th Avenue. Poppi Cottam, whose children—Daphne, Ellie, and Alexi—I had gone to junior high and high school with, brought a different cuisine to the space without changing its essential role. The neighborhood existed in a state of balance then, with Sacred Heart close enough to shape the area’s future, but distant enough, for the moment, to allow an alternative community to persist.

By late 1978, it wasn’t just East 13th that was refining itself. A short walk away, on High Street near the corner of East 12th Avenue, a new coffeehouse and gallery announced itself with a different set of ambitions. A zine article from that fall—“High Street, Now Serving Polite Society” by Lolita Fontaine—captured the moment with a mix of enthusiasm and side-eye that felt exactly right. The coffeehouse wasn’t trying to overthrow anything. It was, as the piece put it, “hoping to attract a more cerebral crowd of conversationalists instead of a mob of rabble-rousers itching to stick it to the man.”

High Street Coffee Gallery occupied “a cozy house built at the start of the Mexican Revolution,” a detail included not for historical precision so much as mood. The proprietors, Ann Blandin and Josephine Cole, were described as “striving to create a more European-style esthetic rather than a beat vibe.” Not that “radical beatniks in Eugene won’t dig it,” the article allowed, but the intent was clear: this was a place for hanging out, sipping coffee, and exchanging ideas, not for posturing.

The house did most of the convincing. It had a fireplace, high-ceiling rooms, large windows, and creaky floorboards. The sign out front set the tone: a painted gentleman in a top hat pouring coffee for a bonneted lady, signaling a space that valued manners, wit, and a certain performance of civility.

Culture extended to the plate. The article lingered over the pastries, singling out a “fancy French pastry called Paris-Brest,” described as “a delectable almond-encrusted bicycle-wheel-shaped pâte à choux filled with praline cream.” It was a declaration of seriousness, indulgence, and attention to detail.

Best of all was the food coming out of the kitchen. Lenny Nathan was the in-house chef, already known around town for the cheesecakes he and his daughters made and sold at the Saturday Market—chocolate rum foremost, but also strawberry, eggnog, and plain. Lenny had moved to Eugene earlier that year to open a restaurant with his son, Nano. “That restaurant fell through,” the article noted, but the tone was forgiving. He treated it as a temporary setback, cooking instead for the coffeehouse: daily soups with locally made French bread, Saturday brunch omelettes, Sunday brunch crêpes.

The rest of the details completed the picture. Classical or jazz played in the background. The art on the walls was local. A brick patio offered outdoor seating. Chess players were welcome, and boards were provided. Smoking was prohibited. The hours ran long. The place was clearly designed to support conversation without rushing it along.

Seen in context, High Street Coffee Gallery wasn’t a rejection of what had been happening on East 13th so much as a refinement of it. Books, cafés, food, art, and talk were still the organizing principles. Where East 13th had grown organically out of former houses and shared necessity, High Street made its intentions explicit. It wanted thoughtfulness. It wanted civility. It wanted a place where ideas could be exchanged without anyone feeling the need to stick it to the man first.