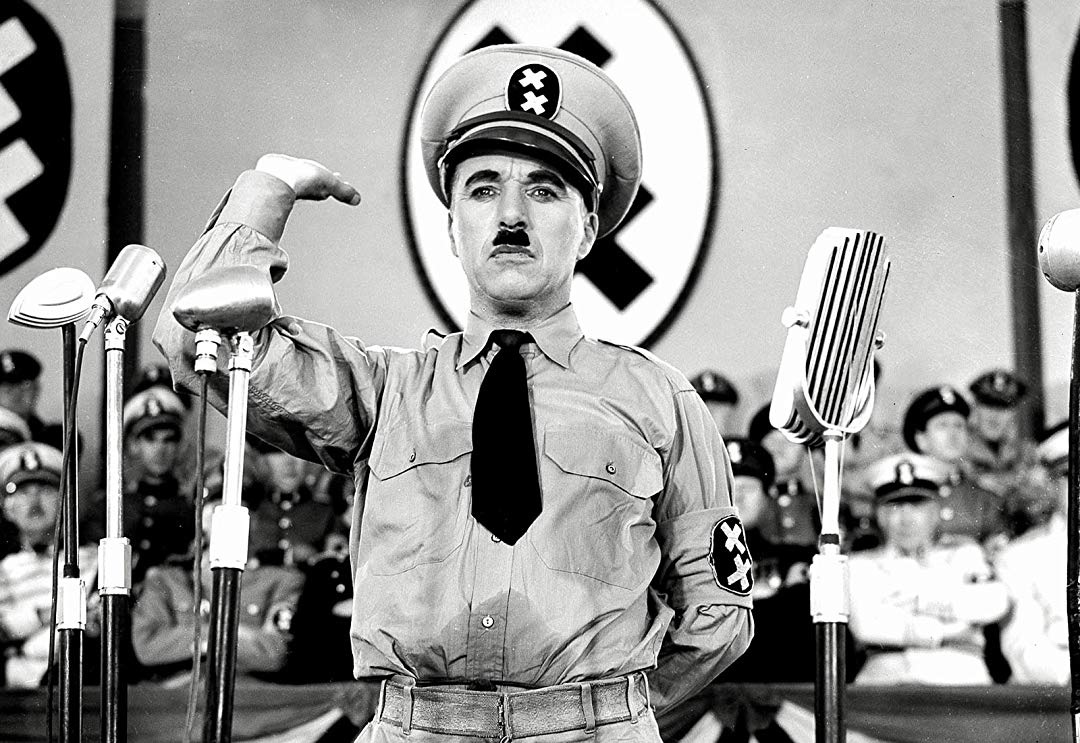

The Great Dictator (1940) was Charlie Chaplin’s first talking picture and the film is a magnificent parody and a scathing condemnation of fascism and Adolf Hitler. The movie was still in production in 1939 when Britain and France declared war on Germany on Sunday, the 3rd of September, and Chaplin heard “the depressing news” over the radio while he was on his boat in Catalina over the weekend. The allies could no longer stay out of the fight after the invasion of Poland by German forces two days earlier and the news was delivered in depressing tones by British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain.

Two years earlier, in 1937, when war was in the air and Nazis were on the march, Charlie was struggling to write a story and a role for his twenty-nine year old wife, Paulette Goddard, who had shot to fame the previous year as leading lady to Chaplin’s character, the tramp, in Modern Times.

“How could I throw myself into feminine whimsy or think of romance or the problems of love,” Charlie would later write in his autobiography, “when madness was being stirred up by a hideous grotesque, Adolf Hitler?”

Enter, friend and fellow filmmaker, Alexander Korda—whose own wife, film actresss Maria Corda, was unable to make the artistic transition from the silent era to the emerging age of the talkies because of her strong Hungarian accent. Korda made the audacious suggestion to Chaplin that he make a film about Hitler based on mistaken identity, because the resemblance of Charlie’s famous fictional character, the tramp, was often compared to the infamous real world character of the dictator, as they both sported the same sort of mustache.

Coincidentally, Chaplin and Hitler shared other similarities, in addition to the style of the hair below their noses. Born four days apart in April of 1889, both men idolized their mothers, had ugly drunks as fathers, and had risen to success from the experience of living in great poverty. They were also both consummate actors.