The New World Coffee House, a Eugene, Oregon establishment that opened in 1964, was a gathering place reminiscent of the bohemian cafés of San Francisco and Berkeley. It attracted the university’s political crowd, hosted live music and art shows, and served as a hub for tarot readings, quiet contemplation, and grassroots organizing. It was the kind of place where people met to plan protests, form committees, and discuss current affairs.

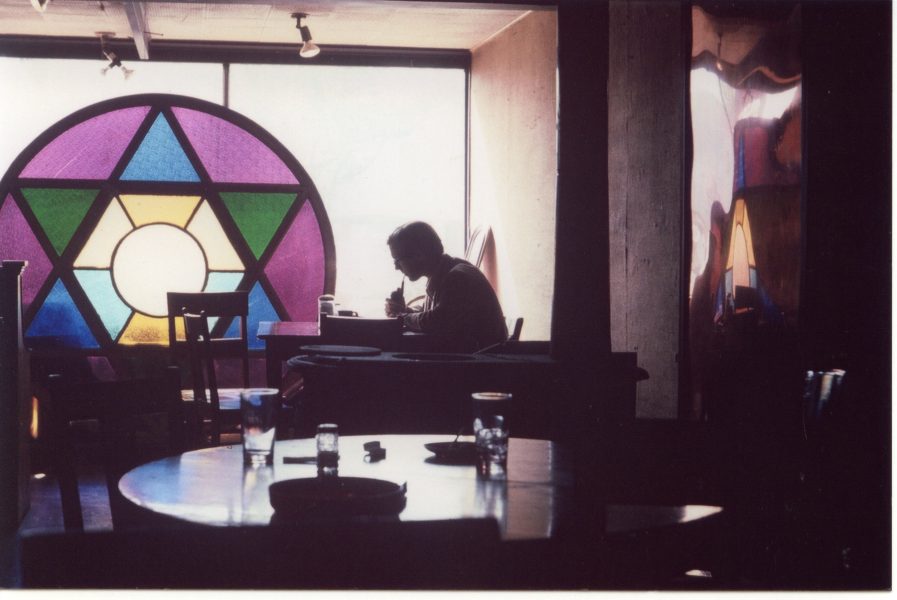

Its owner, Vic Sabin, remodeled the interior of the building at 1249 Alder Street using salvaged fixtures, doors, and stained glass windows from torn-down houses, giving the space a distinctive bohemian aesthetic. The café featured round tables made from wooden spools alongside square café tables, while a long communal table in the back encouraged socializing. A funky old piano stood in one corner, which Jerry Rust, founder of the Hoedads, remembers his friend Scott Bartlett using to deliver laid-back sounds that enhanced the atmosphere. A large wood stove provided warmth during chilly Eugene days, with customers often rising from their seats to throw another log in when the café felt cold. A small courtyard behind the coffee house, adorned with tables and plants, provided an inviting outdoor retreat.

Most significantly, New World was the first café in Eugene to serve espresso. At a time when most coffee in town came in the form of percolated diner brews or drip coffee, New World introduced locals to freshly pulled espresso shots. The café also served coffee made in beautiful handblown Chemex carafes kept warm in water baths, using overroasted beans from Capricorn in San Francisco. The café set a new standard, paving the way for the city’s evolving coffee culture and inspiring future coffeehouses to follow suit.

Beyond its pioneering role in Eugene’s espresso culture, New World was also the first café in town to use Torani syrups to flavor specialty espresso drinks. It introduced Amalfi sodas, its own version of the Italian soda that had been popular in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood for decades. The syrups were supplied by Ira Frankel, a local food distributor who sourced them from San Francisco. New World also created a signature drink called a Cappuccino Borgia, made with espresso, chocolate powder, and orange peel, topped with whipped cream. This unique creation lived on long after the café closed—The Coffee Corner kept the drink in circulation in Eugene as a Café Borgia, and Jim and Patty Roberts took the Borgia north in 1976, where it’s still being made at their coffeehouse, Jim & Patty’s Coffee in Portland.

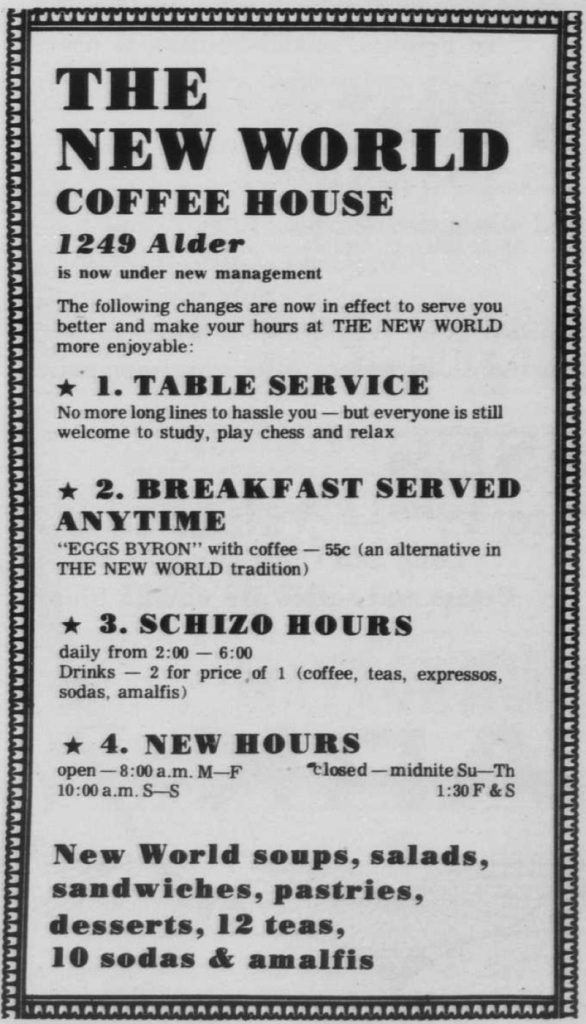

In its early years, New World sold pastries and cakes baked by Stephanie Pearl, who would later open the Excelsior Café. The menu expanded over time to include Hilda’s delicious soups, sandwiches, omelets, bagels, quiche, and more. Rumor has it the San Marino Chocolate Cake was to die for.

In 1968, the same year the Odyssey Coffee House and Theater opened in Eugene, Vic Sabin sold New World to a group of university professors, who attempted to run it as an employee cooperative. However, financial struggles plagued New World under its new management over the next few years.

Economic difficulties, inefficiencies, a huge staff, and a lack of clear leadership hindered its operation. The cooperative model, while idealistic, suffered from communication breakdowns and operational chaos. Maintaining seventeen employees also proved unsustainable.

By 1971, New World shut down, putting up a sign in the window that read: “Closed Forever.” But its story didn’t end there. Under new management, the café reopened a few months later with a leaner staff of just seven employees, all close friends of the new manager, Peter Winograd. This streamlined operation gave New World a second life, but only for a few more years before it finally faded from Eugene’s coffee culture in August of 1974.

———

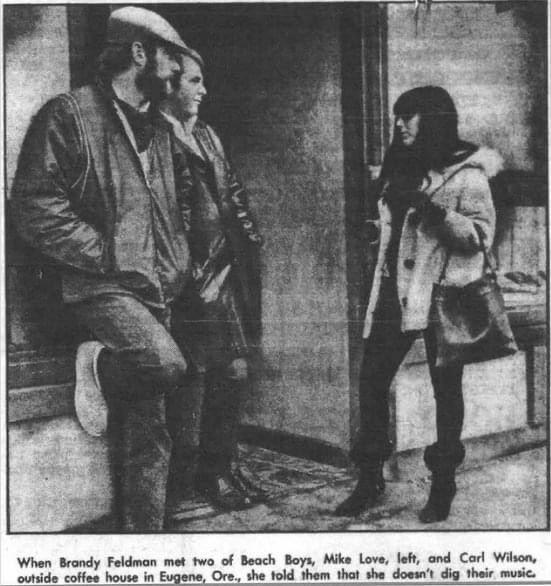

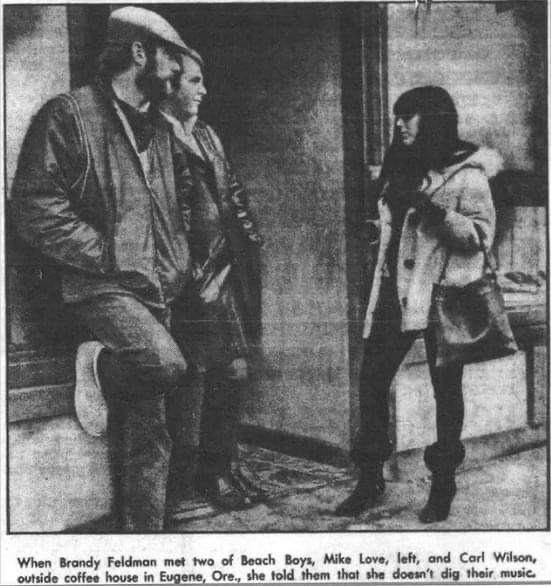

A note on the Oregon Daily Emerald image:

Brandy Feldman, the girl who doesn’t dig Mike and Carl’s music, made the local news the following year when she participated with other college students and SDS members in an unsanctioned afternoon of making street art.

What happened was, on April 12, 1967, a group of so-called beatniks and hippies, armed with colored chalk, wrote slogans and drew flowers and other symbols of peace and love on the sidewalk in front of the student union. The backlash from the football-fraternity mentality for this “chalk-in” was swift, as members of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity (already notorious on campus for hippie baiting) responded first with threats of violence against the group, and then with spitting, shoving, kicking, and pulling hair.

By the end of the fracas, the ATO frat-bros dumped buckets of water on the sidewalk to erase the hippie graffiti that had so offended them.