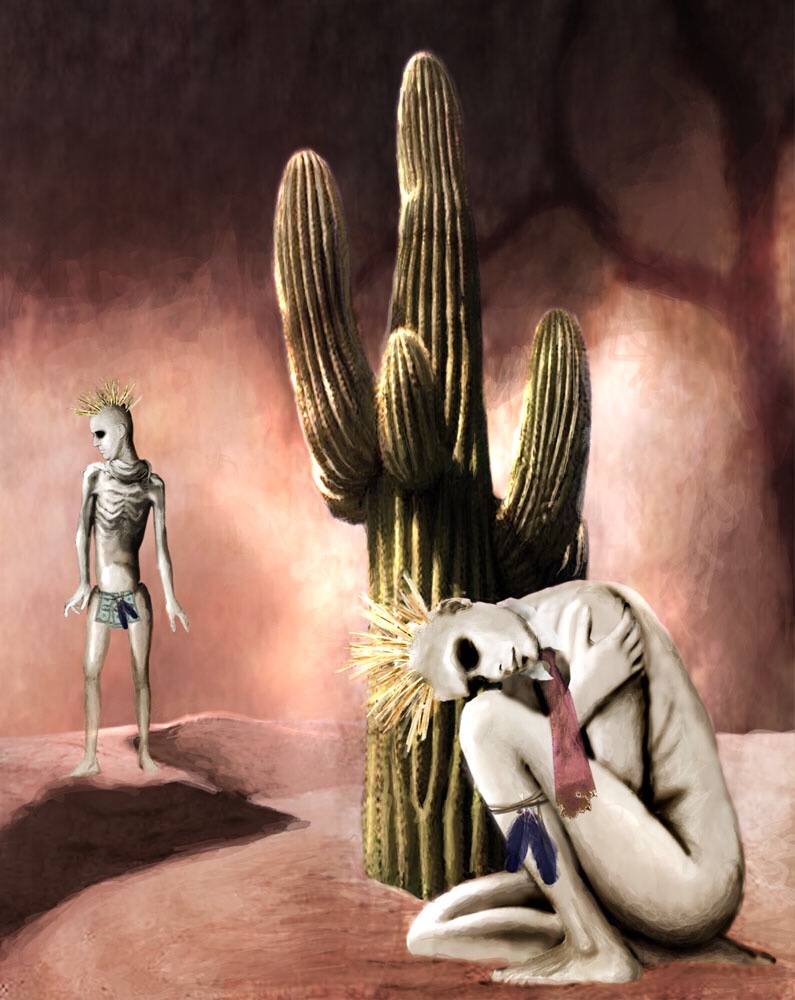

I enter the Literary Salon and shake the debris of popular kitsch off my overcoat, turning a deaf ear away from the hue and cry of current American politics as I begin hanging on the Gallery wall paintings of half deserted streets shrouded in yellow fog, bowls of uneaten peaches, sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown, and scenes from the cactus land.

Seated in the guest chair is my friend, Thomas Stearns Eliot, one of The Grand Masters of Poetry—born on this day a hundred and thirty years ago in St. Louis, Missouri, on 26 September 1888. Thomas (known to the world as T.S.) is in the Salon to regale us with two glorious heirs of his invention.

Now, every published poet has a first born child of the muse that is presented to the world but not every fruit of the brow is heralded as the second coming.

T. S. Eliot, back at Harvard after a year spent studying philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris, was a month shy of his twenty-third birthday when he finished composing The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in August of 1911.

A few years later, as Eliot was just beginning his life-long expatriate act in England, the poem came to the attention of Ezra Pound — who was acting as foreign editor of Harriet Monroe’s Poetry: A Magazine of Verse — and Pound urged Monroe to publish it—gushing that young Eliot “has actually trained himself and modernized himself on his own.”

The year 1915 was filled with the sensational and it began with a story of a hospital cook named Typhoid Mary in New York City. The Great War in Europe was spreading rapidly like a cancer from the center and fears of death and disease were a constant preoccupation. News that more than 29,000 people had perished by a massive earthquake in Avezzano, Italy married the unnatural with natural disaster.

One form of defiance was embodied by a straitjacketed Harry Houdini, spurning the advances of his would-be lover, Death—and The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock was published in the June 1915 issue of Harriet Monroe’s magazine

For those with a finely tuned poetic ear in that second decade of the 20th century it was a revelation.

The Love-Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915)

Some of us living in the century after Prufrock was written may find it amusing that a comparison of the evening sky to a patient etherised upon a table was considered shocking and offensive at the time. To me the poem has a timeless feel that people of any age can understand—a stream of conscious lament of a man characteristic of the Modernists of the time that seems just as relevant now as it did in the last century.

Ten years later, Eliot would give us another masterpiece of poetry.

The Hollow Men by sive.

Stay as long as you wish in the Salon (after the cups, the marmalade, and the tea), away from the kitsch and oblivious to the hue and cry…and go deeper into these two songs of humanity.

In this last of meeting places we can cast off deliberate disguises, disturb the universe, and talk of Michelangelo.

***

A different version of this piece first appeared in the online magazine Rebelle Society on 7 October 2012