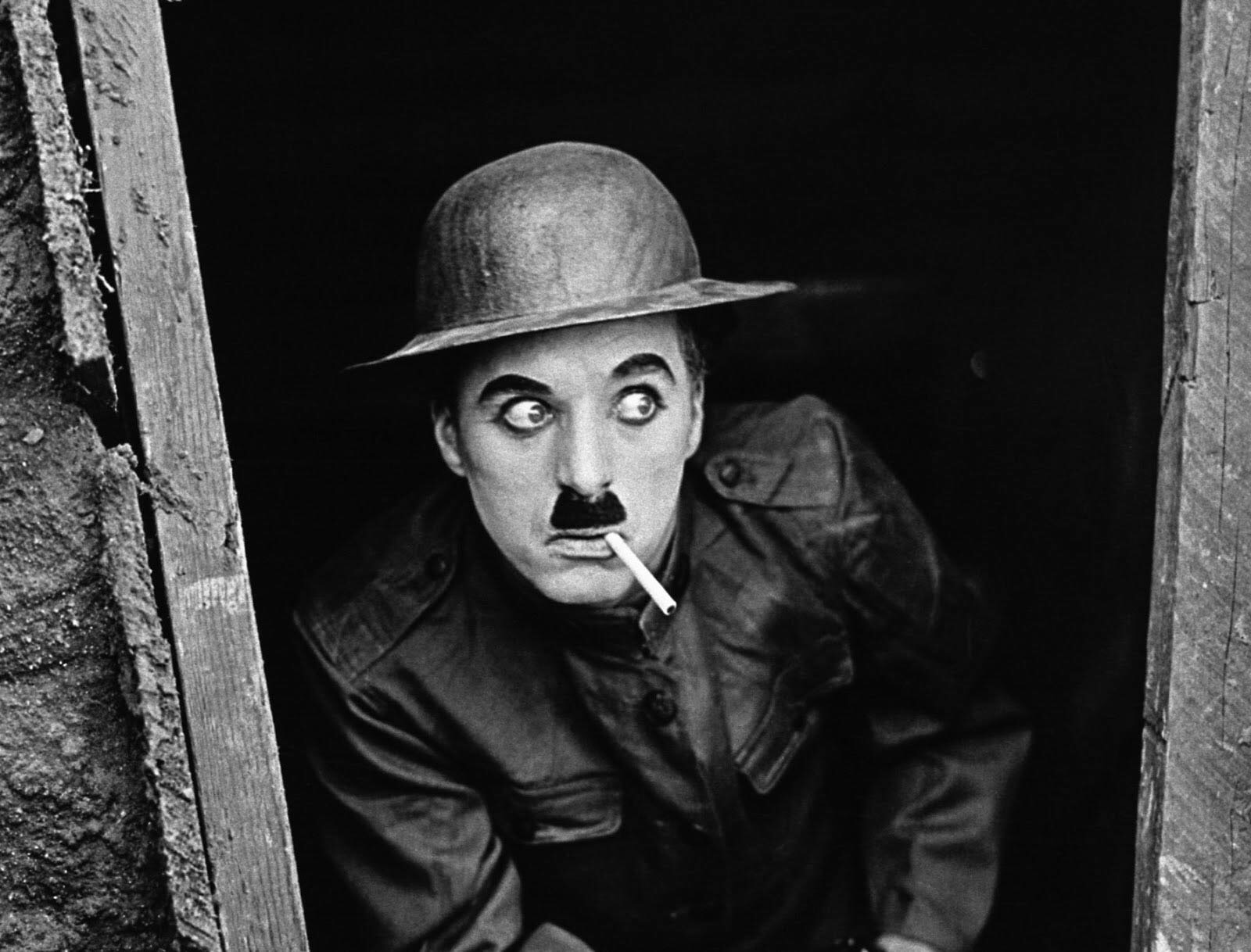

I’m in a pub with Charlie Chaplin and he’s regaling me with one version of his history. He says he was born into poverty amid the squalor of South London on 16 April 1889—the same year that the Moulin Rouge opened in Paris. Charlie’s birth took place in a gypsy caravan as it was traveling through Birmingham. His mother, Hannah, would never tell Charlie who his father was or if she even knew.

The funny thing about this interview is that Chaplin’s lips are moving but no sound is coming out. Of course, he’s a silent movie star, I should have expected a dumb show. Fortunately, there are subtitles in my mind.

Chaplin started as a music hall performer among comics and mimes and magicians and mesmerists, performing before booze soaked audiences that watched the acts through a haze of tobacco smoke. At eighteen, he joined Fred Karno’s burlesque of mimes and acrobats. Karno, a theater impresario and comedian, was known as the father of the custard-pie-in-the-face gag—and Charlie was still with Fred Karno’s Army in the autumn of 1910 when the touring company left Southampton aboard the SS Cairnrona and crossed the Atlantic bound for Canada.

Not surprisingly, a piano crashes through the ceiling above and crushes our table, depositing an unkempt Stan Laurel at our feet. I’m reminded of Slim Pickens riding an atomic bomb at the end of Doctor Strangelove.

Stan dusts the ceiling plaster from his suit and says, “I was Charlie’s understudy and room-mate for the tour. When we reached the shores of Quebec, we were all on the deck of the [converted cattle boat], sitting, watching the land in the mist.”

Suddenly, Charlie ran to the railing, took off his hat, waved it and shouted:

“America, I am coming to conquer you! Every man, woman and child shall have my name on their lips—Charles Spencer Chaplin!”

“We all booed him affectionately and he bowed to us very formally and sat down again.”