When I lived in California, I loved riding my Vespa from my home in Santa Rosa to Jack London State Park in Glen Ellen.

On the way, I’d stop at Les Pascals Patisserie et Boulangerie to write and watch the charming Parisian owners work and chat with customers. Monsieur Pascal was typically in the kitchen baking while Madame Pascale was at the counter working the register. It was a pilgrimage for many regulars to go there and practice their French. I’d say: “Bonjour, Madame Pascal! Ça va?” I always asked for “un pain au chocolat et un café crème, s’il vous plaît.”

Around the corner and a mile up London Ranch Road, the burned-out stone walls of a house stood—half ruin, half reliquary—like a literary necropolis. Jack London poured years of money, muscle, and yearning into building his redwood-and-stone dream home. Wolf House was nearly finished when, in the early hours of August 22, 1913, a fire ravaged the entire structure before he spent a single night inside. Jack was devastated.

Three years later, on November 22, 1916, he died at the age of forty.

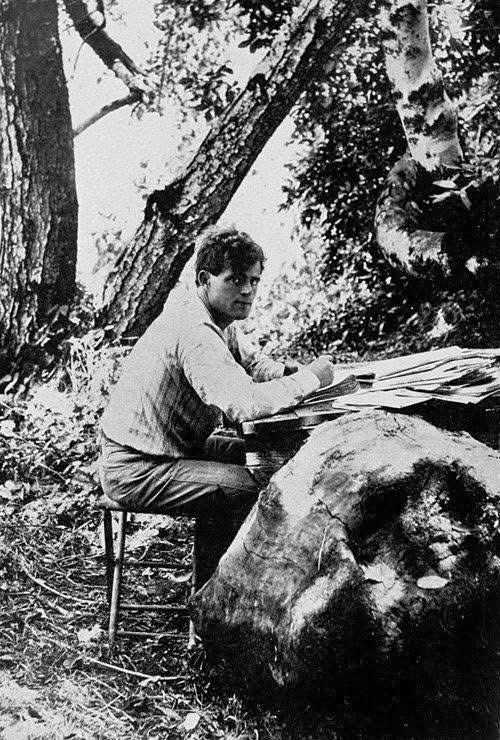

Daydreaming under the cork oaks, I imagined Jack barreling through life with his impossible schedule. So many books, so many articles, and so much ambition for one human metabolism. And toward the end, too much alcohol, too much pain, and two kidneys giving up in despair. His cause of death—from dysentery, uremia, morphine, opium, and late-stage alcoholism—reads like a checklist of self-destruction. I’ve always believed he also died of sorrow. Whatever the cause, Jack London wrote like a machine and wrote to exhaustion. He burned hot, then burned out.

Today, on the anniversary of his death, I’m thinking about Jack London not as the heroic adventurer or the big-jawed socialist sailor-prophet, but as a fellow worker in the mines of language.

He left behind a heartbreaking record of what happens when talent, trauma, substance abuse, and the American drive to produce collide in one short, incandescent life.

~ Richard La Rosa