Some days, the page needs a rest from creation. Those days are perfect for transcribing.

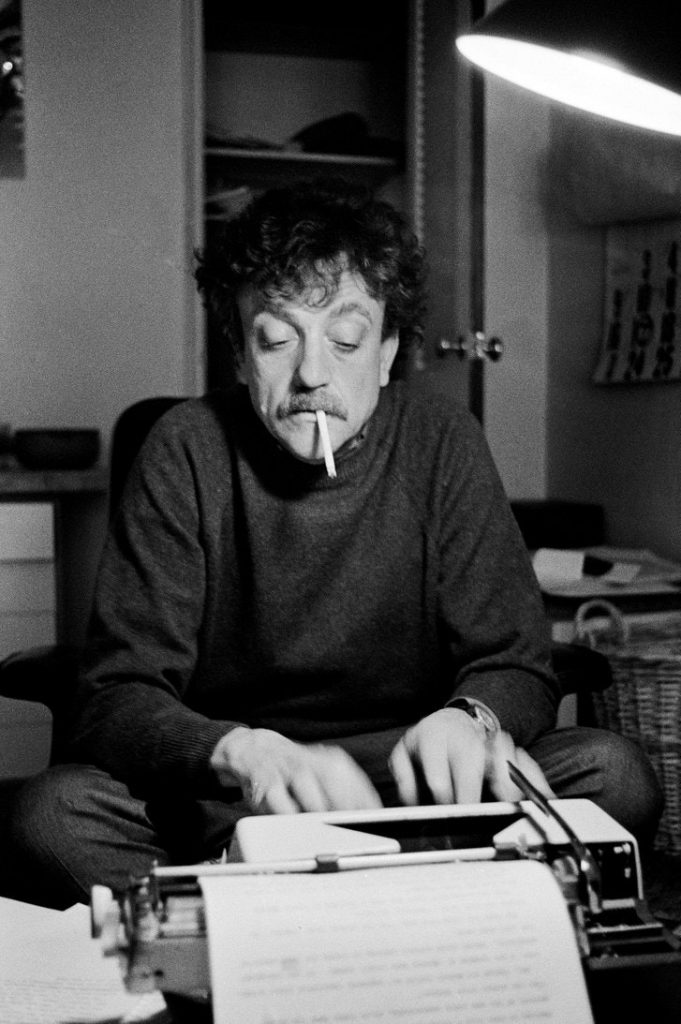

Kurt Vonnegut wrote a scene in Cat’s Cradle where a “vacantly pretty” secretary says she knows nothing about surface chemistry, even though she types for a famous chemist every day.

“Don’t ask me,” she says. “I just type what he tells me to type.”

The narrator observes that her smile is glassy and her mind contains nothing but used Kleenex and costume jewelry. Harsh.

She was a believable character for 1963.

But 1963 was also the year my grandmother sat at a typewriter as a medical transcriptionist.

She soaked up everything — every term, every diagnosis, every procedural note.

Decades later, she would casually rattle off medical facts at the dinner table with the confidence of a seasoned clinician. She wasn’t pretending. There was no imposter syndrome. She had learned it through repetition, curiosity, and attention.

I’m like her that way. I’m a knowledge junkie. I don’t understand willful ignorance, especially from people who work close to knowledge every single day. If information passes through your hands, why not catch some of it?

Transcribing stories is a way of catching knowledge — your own knowledge.

You’ll hear how you speak, how you ramble, where the emotional gravity sits.

You’ll notice patterns you didn’t know were there.

Here’s the practice:

Take a minute or two and record yourself telling a story you’ve told before but never written down and transcribe it.

Or transcribe a half a page from an audiobook if you cannot speak.

It doesn’t have to be word-for-word. You’re a writer discovering how ideas sound when they arrive through your mouth instead of your hands, not a court reporter.

I’ve transcribed conversations and passages from books just to understand them better. There’s a particular magic that happens in transcription. It’s the ingredients of the spell. The potion is brewed later through rewriting and revision.

Transcription is a shortcut that injects words directly into a writer’s brain

Start with sound, finish with ink.

~ Richard La Rosa