I want to write. But . . .

Suddenly, I’m transported to the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, twenty-five years in the past, and I’m standing by the grave of Jean-Dominique Bauby—paying my respects with a pot of chrysanthemums.

I open my journal and read some French words I’ve transcribed and translated into English, sourced from a book called Le Scaphandre et le Papillon. The English version is called The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

Derrière le rideau de toile mitée une clarté laiteuse annonce l’approche du petit matin.

Behind the linen curtain a milky clarity announces the approach of dawn.

J’ai mal aux talons, la tête comme une enclume, et une sorte de scaphandre qui m’enserre tout le corps.

My heels hurt, my head is like an anvil, and a sort of spacesuit seems to surround my whole body.

Ma chambre sort doucement de la pénombre.

My room slowly emerges from the shadows of twilight.

These sentences were “written” by a writer unable to use his hands to type words, communicate through gestures, or to speak words to be transcribed by another writer. The following italicized words are from the English version of the book:

No need to wonder very long where I am, or to recall that the life I once knew was snuffed out Friday, the eighth of December, last year.

Up until then, I had never even heard of the brainstem. I’ve since learned that it is an essential component of our internal computer, the inseparable link between the brain and the spinal cord. I was brutally introduced to this vital piece of anatomy when a cerebrovascular accident took my brain stem out of action.

The accident that rendered Jean-Dominique Bauby mute and immobile?

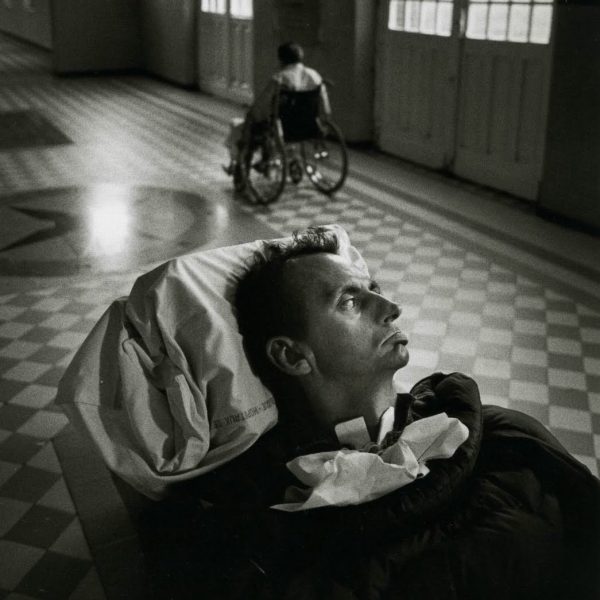

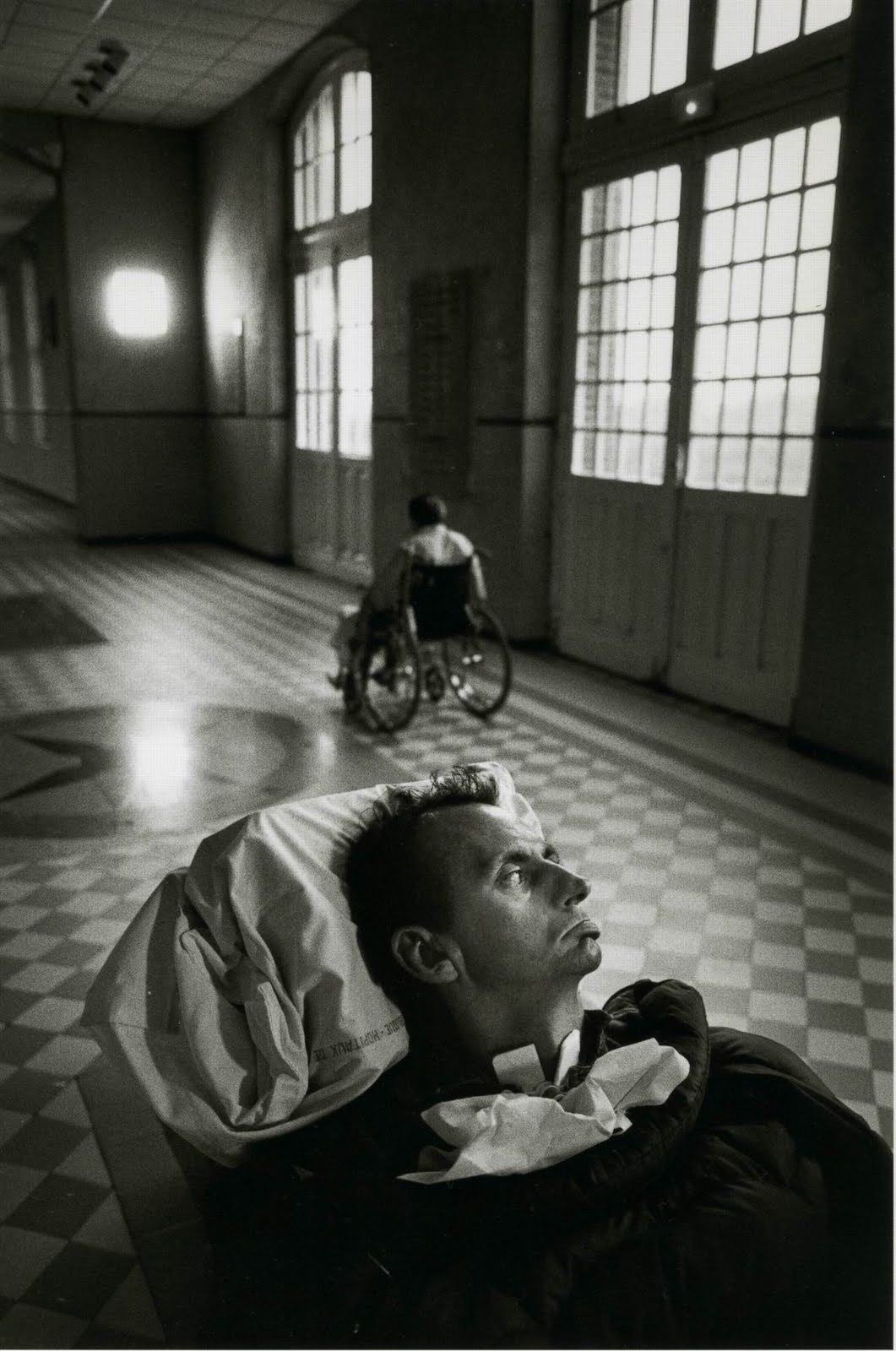

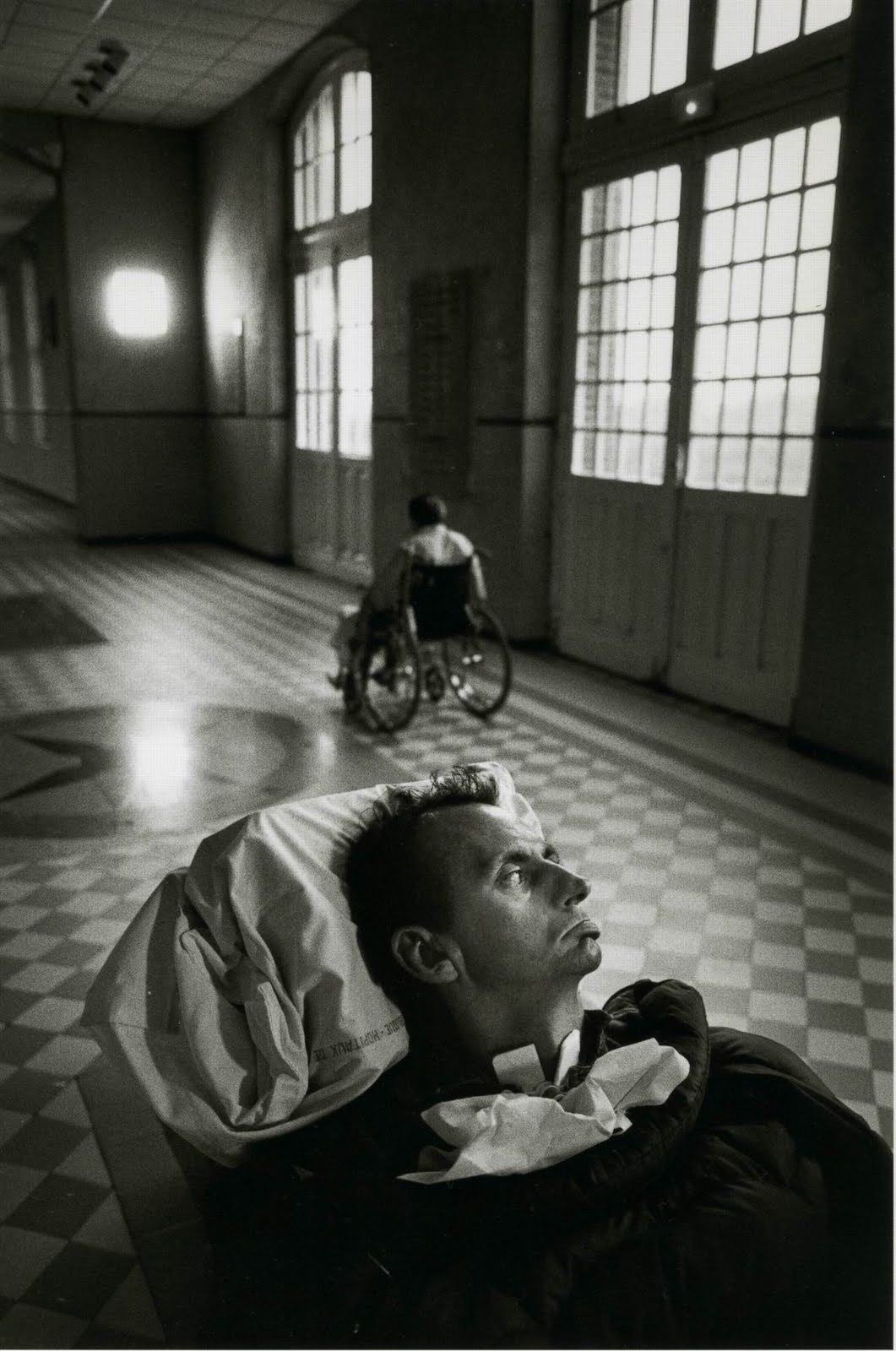

In the past, it was known as a massive stroke, and you simply died. But improved resuscitation techniques have now prolonged and refined the agony. You survive, but you survive with what is so aptly known as “locked-in syndrome.” Paralyzed from head to toe, the patient, his mind intact, is imprisoned inside his own body, unable to speak or move.

But, how was Jean-Dominique able to communicate the words you’ve just read if he was unable to speak or move?

In my case, blinking my left eyelid is my only means of communication.

What?

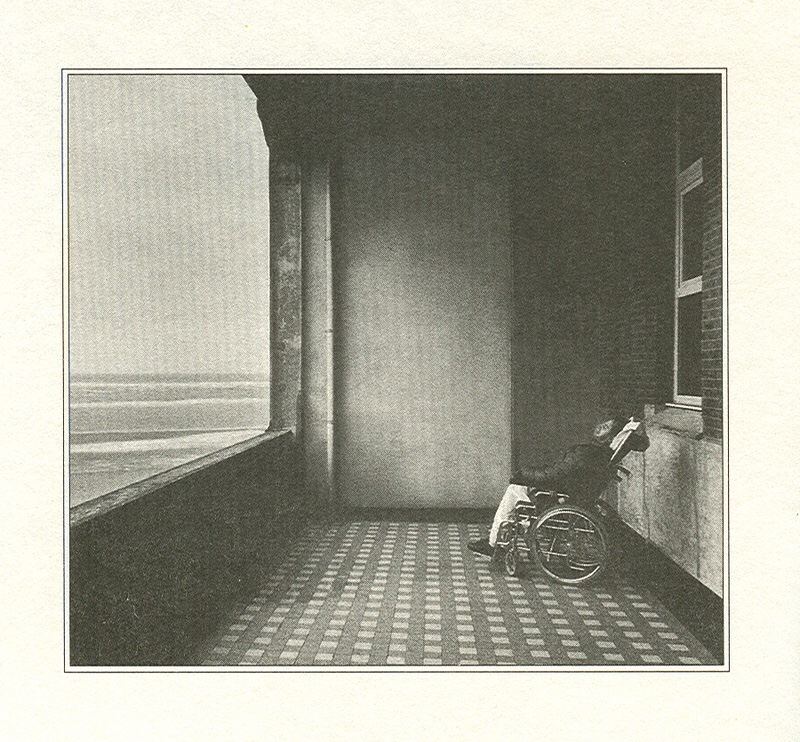

Of course, the party chiefly concerned is the last to hear the good news. I myself had twenty days of deep coma and several weeks of grogginess and somnolence before I truly appreciated the extent of the damage. I did not fully awake until the end of January. When I finally surfaced I was in room 119 of the Naval Hospital at Berck-sur-Mer, on the French Channel coast–the same Room 119, infused now with the first light of day, from which I write.

Enough rambling. My main task now is to compose the first of these bedridden travel notes so that I shall be ready when my publisher’s emissary arrives to take my dictation, letter by letter.

He writes these words by dictating his memoir, one letter at a time, to his clever and efficient conversational co-conspirator, Claude Mendibil, who lists the letters in accordance with their frequency in the French language.

In my head I churn over every sentence ten times, delete a word, add an adjective, and learn my text by heart, paragraph by paragraph.

By a fortunate stroke of luck and intuition Jean-Do’s physical therapist noticed that he could blink his left eyelid—his paralyzed right eyelid had been sewed shut to prevent his eyeball from drying up—and she had devised a communication system called partner-assisted scanning, which utilized his singular muscular ability to dictate a beautiful memoir.

It is a simple enough system. You read off the alphabet (ESA version, not ABC) until, with a blink of my eye, I stop you at the letter to be noted. The maneuver is repeated for the letters that follow, so that fairly soon you have a whole word, and then fragments of more or less intelligible sentences. That, at least, is the theory. In reality, all does not go well for some visitors. Because of nervousness, impatience, or obtuseness, performances vary in the handling of the code (which is what we call this method of transcribing my thoughts). Crossword fans and Scrabble players have a head start. Girls manage better than boys. By dint of practice, some of them know the code by heart and no longer even turn to our special notebook—the one containing the order of the letters and in which all my words are set down like the Delphic oracle’s.

And what are those travel notes of which Bauby babbles about? They’re excursions of the imagination, of course—the only recourse for a traveler physically bound and rooted in place like an oak tree. His thoughts branch out, stretching beyond the boundaries of place, allowing his mind (which he likens to a diving bell) to take flight like a butterfly.

You can wander off in space and time, set out for Tierra del Fuego or for King Midas’s court. You can visit the woman you love, slide down beside her and stroke her still-sleeping face. You can build castles in Spain, steal the Golden Fleece, discover Atlantis, realize your childhood dreams and ambitions.

Ten months and two hundred thousand blinks later, Jean-Do completes his magnificient memoir and expires from pneumonia on March 9th, 1997, two days after his book is published.

***

Returning to the present and presented with my first thought—

I want to write . . .

The “but” is a needless word that must be omitted. I write without excuses.

Like this:

Like Loading...