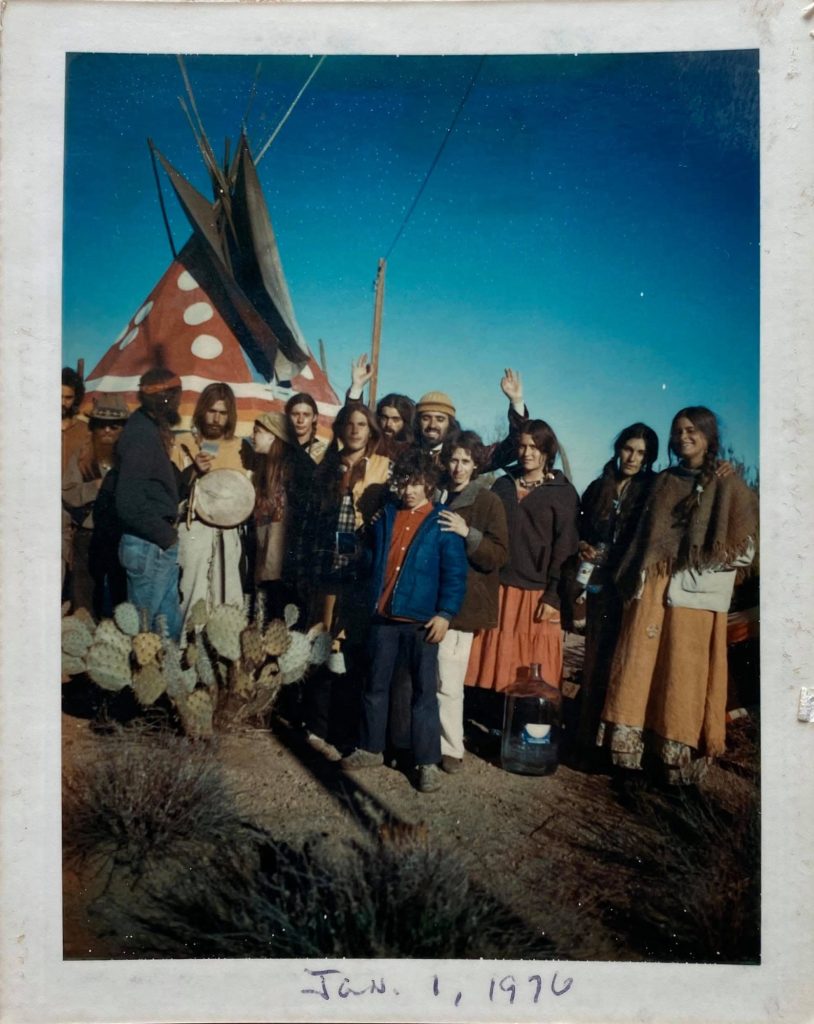

Tucson, Arizona (1976)

I’m eleven years old, half feral, and worn out from constantly getting into fistfights with boys who call me a long-haired hippie freak. They’re not wrong. I spend my days barefoot and sunburned, and my tolerance for bullshit is zero.

My dad is out of it. He’s going through some heavy shit and has that thousand-yard stare of a shell-shocked Vietnam vet. I don’t really understand the details, but I don’t have to. It’s been a hell of a year, and it’s only April.

Dad’s girlfriend Linda ditched us back in March. She took off with my baby brother in the bread truck we’ve been living in since ’72. She beat me to the exit. I was ready to bolt in January, right after the cops raided our desert commune during a peyote ceremony. I had a plan and a partner in crime, but my partner’s little sister squealed, and we got nabbed.

Without Linda in the picture, I figure we’re headed for the streets. But Papa Casanova always lands on his feet. He shacks up with a woman named Jiliflower, who has a two-bedroom house she shares with her twin daughters. This means I get a pallet on the living room floor, because she’s already taken in another stray who’s claimed the couch. Dad shares Jiliflower’s bed. I share the living room with a guy who shares my name but looks nothing like me.

Richard is short, dark-skinned, with long hair, a Mexican mustache, big teeth, and an all-white wardrobe that smells like Nag Champa. He’s very spiritual.

Me? I’m shorter, skinny, but also muscular from a lifetime of climbing trees. I look like a light-skinned Mowgli or Tarzan’s bastard son, and plenty of people have seen me that way, since I went full native and ran around in a loincloth, with bow and arrows, shooting at saguaros and rabbits. That wasn’t a dream; it actually happened.

Nowadays I’m mostly in grubby thrift-store jeans, shirtless unless it’s cold or I’m trying to pass for civilized.

2.

One morning on Fourth Street, I see Heather and Michael panhandling in front of the Food Conspiracy.

Heather is a very pretty hippie chick, barely in her twenties, with a little boy named Michael who’s maybe five or six. She’s holding a hand-painted sign and her son is sitting cross-legged at her feet, poking at a crack in the sidewalk with a stick. She looks tired, dusty, and still beautiful in that earthy way—sun dress, bare feet, beads, beads, beads.

I met them at Eden Hot Springs near Globe after I rode out there with a bunch of Rainbow Family folks for a healing gathering. My dad was too sick to come along and stayed in Tucson. Funny that people always call them healing gatherings, or festivals, when there’s usually a bunch of people flipping out on psychedelics or puking from spoiled communal stew.

Heather is trying to scrape together money for food and gas because she has this plan to hitchhike up to some land outside of Ukiah in Northern California. Supposedly there are cabins and horses and a bunch of cool people living there. Sounds like a small commune, or at least a place where adults don’t yell at you for running wild while they’re letting it all hang out. Heather doesn’t know much more about the place, but she talks about it like it’s paradise.

It sounds like a dream to me. My earlier plan to run away didn’t have a specific destination in mind, maybe San Francisco or somewhere in Oregon, so this just feels like the sign I’ve been waiting for. I tell Heather I have fifteen bucks saved up from doing odd jobs and I’ll share it if she lets me tag along. I’m thinking I’ll take care of her and the kid, like I’m a grown-up sugar daddy or something. She looks at me like she’s trying to figure out if I’m serious, and I guess I am, because for the first time in years, I feel free.

3.

Most adults I meet are on power trips and treat children like second-class citizens and all my teachers think I’m clueless because I don’t always have the answers they want.

Sure, since third grade I’ve been out of school more often than I’ve been inside a classroom. But that doesn’t mean I’m not sharp, it just means I never bothered to learn that Grover Washington delivered the spaghetti bird a dress in 1492, or some such bullshit. They have no clue I’ve learned to question authority and been lectured by acid-tripping college dropouts from some of the finest universities in the country.

I also read a lot, even though it’s mostly science fiction and comic books.

Many adults in my tribe don’t have strict rules for children because they were raised by strict parents. They prefer to let the little people in their lives experiment, make their own mistakes, and find their own way. That’s what I’m counting on with Heather.

So I tell her I’m a year and a half older than I am because thirteen sounds way more capable than eleven. I figure she’s probably been on her own since she was a teenager, so she’ll get it. I point out the two slim throwing knives in my belt, half covered by my tee-shirt, and the bigger knife hidden under the right leg of my jeans, showing her I’m someone who can protect us if things get hairy. If she’s going to be sticking out her thumb and hitching a thousand miles of rides on Interstate 10, there’s safety in numbers, and I’m her backup.

But maybe I’m trying too hard, because Heather’s got that glazed-over, patchouli-and-weed vibe that says she’s too stoned to make responsible decisions. I crouch down and hand Michael some trail mix as a gesture of friendship. The wind kicks up, a little tumbleweed bumps into me, and I play it up with an exaggerated “ouch” to make Michael laugh.

Little kids love me. I’m the life of the party.

~ Richard La Rosa